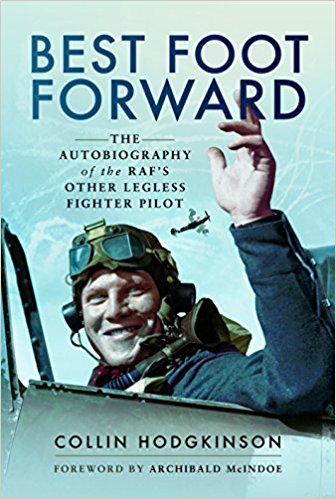

Colin Hodgkinson the other Legless Spitfire pilot!

Many are not aware of the number of aircrew that either battled against disability caused by enemy action or accidents, either physically or mentally to return to operations. Their personal battles hidden from view but always there, each day not taking the fight to the enemy, but also battling against a disability. Many also returned to flying despite horrendous burns, suffering from continued anxiety and flashbacks caused as a result of their trauma such as Flight Lieutenant Richard Hillary who after being awfully burned during action in the Battle of Britain, returned to flying despite his hands being in a terrible state. What pushes these men to overcome such horrendous injuries, to want to return to the environment in which they were nearly killed?

As a lowly Midshipman in the Fleet Air Arm, Colin embarked on his flying career through elementary pilot training on the De-Havilland Tiger Moth at 20 Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School. For most low hour trainee pilots, the anxiety they faced was the fear of underperforming and being washed out, having to re-muster as another trade. For some they just could not get on with just being in the air. For Colin his nemesis at this point in time was learning to fly on instruments, which meant having to pull a canvas hood over his cockpit to simulate flying at night or in cloud with no reference to the horizon. This can be very disorientating for new pilots and for the un-initiated. It is uncomfortable as your body and senses lie to you as you get tossed about in the air or carry out turns. A pilot is taught he must rely on what the instruments are telling him and respond accordingly.

Colin found this extremely claustrophobic and it was not his strong point. He required extra tuition to iron out his problems. It was on one of these extended instrument training flights that unfortunately lead to a potential shortening of Colin's career in the Fleet Air Arm. On the 12 May 1939 Colin took off accompanied by his instructor, Hodgkinson was practicing blind flying on instruments under “the hood” having completed fourteen and a half hours flying so far.

At 4.20pm The Tiger Moth was struck by another in the circuit and his aircraft feel to the earth from 500ft at Gravesend in Kent, killing the instructor and so grievously injuring Hodgkinson that his legs were amputated. One of the eye witnesses of that crash was Tony Phelps who helped pull Colin from the wreckage “a few of us were standing on the airfield watching the plane Colin was in and another, both of which are on blind flying instruction. We could see from the course the planes were taking that a crash was inevitable. Another chap and I jumped into my car and we rushed over. Wreckage was spread everywhere. We managed to drag Colin out and did what we could until the proper rescue squads arrived. I can tell you I never thought he would live, much less fly”.

Colin was badly injured and was taken to Gravesend hospital for a double amputation – the right leg above the knee, the left leg below it. That could have been the end of his naval and flying career. During a long period in hospital he encountered Sir Archibald McIndoe who invited him to his celebrated wartime RAF plastic surgery unit at the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, for some work on his face. During the winter of 1939 he was still struggling and convalescing as his left leg would not heal. It was during this time that he read a story of Douglas Bader who as a pre-war regular had also undergone amputation post flying accident but managed to convince the powers that be that he could return to flying.

Although Colin almost loathed flying he was taken by the story of Douglas Bader and indeed wrote to him, the response was encouraging and Colin was determined to return to flying despite the fact that he wasn’t a natural pilot or that he loved flying. He felt that he must overcome his fears more for himself rather than anything and that flying owed him a living. To that end he approached the surgeons to amputate the remaining left leg that was not healing so that he could start the process of getting back to flying with prosthetics as had Douglas Bader.

By Christmas 1940, he found he could walk perfectly well with his artificial limbs and was determined to go on flying. He joined the RNVR and went on several flights including a trip to Brest as a rear gunner.

In 1941, the Admiralty posted him to elementary training school which he completed and was promoted to sub lieutenant and passed on to intermediate flying training school where he qualified as a pilot. Colin was not satisfied with this and wanted to get into action, so he applied for a transfer to the RAF which was granted. In September 1942, he transferred to the RAF as a pilot officer and on the 19th of that month flew a Spitfire for the first time at RAF Aston Down.

His first posting was briefly with 131 Squadron, a Spitfire unit at RAF Westhampnett at that time under the command of Squadron Leader John Fifield OBE, DFC, AFC. Post war Fifield said of Hodgkinson “it was the 15th of December, 1942, I was commanding 131 Squadron of Spitfires at Westhampnett, a satellite to Tangmere. About 7 in the evening I was in the mess having pre-dinner drinks with some of my pilots when this man (Colin) came in. I knew that he was joining his first operational squadron. I knew that this was to be his baptism of fire. I also knew that he had two artificial legs. I introduced him to the other pilots by the nickname ‘Hoppy’. I didn’t know at the time that by giving him a label I was also giving him a personality. Neither did I know the battle he was fighting with himself”.

Fifield thought that as Hodgkinson had artificial legs that he may need some allowances made for him with regards the distance to his aircraft from his dispersal and also in the location of his accommodation but from the start Colin wanted no special treatment as Fifield continues: - “ I tried to get Colin to take my aircraft dispersal position, which was close to our quarters. He refused, in the same way he refused my room on the ground floor which I offered him to save him climbing the stairs” “he wanted to be treated just like all the others”.

When 131 Squadron were posted out he requested to stay put in the thick of the action. Air Vice Marshall J E “Johnnie” Johnson CB, CBE, DSO**, DFC* post war, wrote about his first meeting with Colin as he was at the time the commanding officer of 610 (County of Chester) Squadron. When the squadron moved into RAF Westhapmnett, Colin applied for a transfer to stay in the front line and Johnnie had picked up that there was something special about Colin and that he was certainly one determined character:-

“Hoppy” Hodgkinson had spent no more than a month with 131, and in that time had flown on only four operational patrols. Then the squadron, due for a rest, was ordered to Castletown on the north east coast of Scotland. It was unusual that a pilot should be transferred from one squadron to another at the very outset of his career” Colin was called to an interview with Johnnie regarding his request to remain at Westhampnett with the new incoming squadron.

“I had to know why this pilot had elected to remain in the front line at this particular moment, just as we fighter pilots were having a very lean time. We exchanged the usual pleasantries and then I asked him why he was so determined to remain in the south. He said something about having to fight against the Luftwaffe to prove himself, and I vaguely sensed that he had grave doubts about his own ability and was seeking to establish his own destiny. I realized that I was only groping for the edges of his problem, but the war was on and what a squadron commander had to look for in his pilots was flying ability, team spirit and aggression. I decided that I might find all of these qualities in Hodgkinson”

Johnnie was proved right and Colin flew many sweeps over occupied France. The following March he was promoted Flying officer and in June joined 611 (County of West Lancashire) Squadron, then in the famous Biggin Hill wing. Not only did Colin master his fears but also started to rack up his score, claiming two FW 190s destroyed and a Bf 109 damaged whilst flying with 611 Squadron. He was subsequently posted to 501 Squadron in November 1943 as a flight commander and it was whilst with this unit that he undertook a high altitude weather reconnaissance in a Spitfire IX, MJ117. Unfortunately his Oxygen supply failed at 30,000 feet and he was to crash land east of Hardelot. The aircraft was such a mess that the Germans had to cut Colin out with an oxy-acetylene torch. He was taken to a hospital at St Omer where he came round after being knocked senseless. Whilst a POW he had a series of operations to sort out his terrible injures to his face and head which were badly injured in this crash. During his internment he lost a lot of weight, to the point that his artificial legs did not fit and he was and was in constant pain. Not one to sit and mope, Colin was not going to sit around and complain about his miss fortune. One of his fellow POWs a chap by the name of Marcus Marsh said of him “he was always cheerful. A fine example to those who took captivity badly”.

He was subsequently re-patriated 10 months after his crash due to his disabilities. For many surely this would have been enough. Had he not proved himself already, he was a successful fighter pilot and flown in the front line since his posting to 131 Squadron. Colin felt that flying owed him a living and so it was he returned to flying once again, this time on a ferry unit at Bristol’s Filton airfield and again post war he retruned to fly the De Havilland Vampire in the Royal Auxiliary Air Force with 501 and 604 Squadrons.

Colin often referred to himself as the “poor man’s Bader” but nothing could be further from the truth, this is the remarkable story of one man’s battle against adversity, his struggle against disability and also a fear of flying. For me this man is a true unsung national hero and I commend his story to the readers. He is was certainly not second best to any one, the final words said by Johnnie Johnson when being interviewed about Hodgkinson on BBCs “This is your life program in 1957 certainly say it all about Colin Hodgkinson “ He was determined to be as good as his colleagues who were not disabled. He was a very brave man”.